We have decided to create the most comprehensive English Summary that will help students with learning and understanding.

The Bond of Love Summary in English by Kenneth Anderson

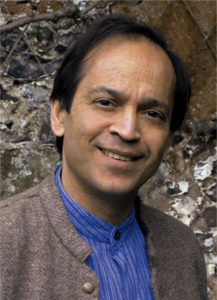

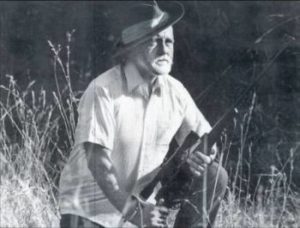

The Bond of Love by Kenneth Anderson About the Author

Kenneth Anderson (1901-1974 ) was an Indian-born, British writer and hunter who wrote books about his adventures in the jungles of South India. His love for the inhabitants of the Indian jungle led him to big game hunting and to writing real-life adventure stories. He often went into the jungle alone and unarmed to meditate and enjoy the beauty of untouched nature. Anderson’s style of writing is descriptive, as he talks about his adventures with wild animals.

While most stories are about hunting tigers and leopards—particularly man- eaters—he includes chapters on his first-hand encounters with elephants, bison, and bears. There are stories about the less ‘popular’ creatures like Indian wild dogs, hyenas, and snakes. He explains the habits and personalities of these animals. Anderson gives insights into the people of the Indian jungles of his time, with woods full of wildlife and local inhabitants having to contend with poor quality roads, communication and health facilities. His books delve into the habits of the jungle tribes, their survival skills, and their day-to-day lives.

| Author Name | Kenneth Anderson |

| Born | 8 March 1910, Bengaluru |

| Died | 30 August 1974, Bengaluru |

| Education | St. Joseph’s College, Bishop Cotton Boys’ School |

| Nationality | British, Indian |

The Bond of Love Introduction to the Chapter

The Bond of Love is a touching account of an orphaned sloth bear who is rescued by the author, Kenneth Anderson, and gifted to his wife as a pet. Bruno, the playful baby bear, gets attached to her, but as he grows in size he is sent to a zoo. When the author’s wife goes to meet Bruno at the zoo, they realise how much the bear loves her and misses her. With the permission of the superintendent of the zoo, they bring Bruno back home. At home, a separate island is made for the animal where the author’s wife and the bear spend hours together.

The Bond of Love Summary in English

Once, Anderson and his companions were passing through sugarcane fields near Mysore when they encountered wild pigs that were being driven away from the fields. Some of them had been shot dead, while others had fled. They thought that everything was over when suddenly a black sloth bear appeared and one of the author’s friends wantonly shot it dead. Soon they discovered that a baby bear had been riding on the back of the mother bear that had been killed. Distressed, the young cub ran around its prostrate parent making a pitiful noise.

Anderson tried to seize the cub, but it ran off into the sugarcane fields, only to be chased and finally captured by the author. He presented the young bear to his wife who was delighted with it. She at once put a coloured ribbon around its neck, and after discovering it was a male cub she named it Bruno. At first, the young bear drank milk from a bottle but soon he started eating all kinds of food. He would eat porridge, vegetables, fruit, nuts, meat, curry and rice regardless of spices, bread, eggs, chocolates, sweets, pudding, ice-cream, etc., etc., etc. As for drink, Bruno drank anything including milk, tea, coffee, lime-juice, aerated water, buttermilk, beer and alcoholic drinks. It all went down with relish.

Bruno became very attached to the two Alsatian dogs that the family owned as well as with the children of the tenants. He enjoyed complete freedom and played and moved about in every area of the author’s house, including the kitchen, and even slept in their beds.

One day, Bruno met with an accident. He entered the library and ate some of the barium carbonate, a poison, that the author had kept to kill the rats. The poison soon showed its effect and Bruno suffered an attack of paralysis. However, he managed to reach the author’s wife who at once informed her husband. Bruno was immediately taken to a veterinary doctor who administered two antidote injections of 10 cc each to the bear. Bruno got well and soon started eating normally. Another time, Bruno drank old engine oil the author had kept as a weapon against the inroads of termites. However, it did not have any effect on him.

The author’s family took good care of Bruno, so he grew at a fast pace becoming many times the size he was when he came. He had become mischievous and playful. Bruno was very fond the author’s family, but he loved the author’s wife above all, and she loved him too! The author’s wife now changed his name to Baba which means a ‘small boy’. He leamt to perform a few tricks as well but still had to be kept chained because of the tenants’ children.

Soon the author and his son, and their friends felt that Bruno should be sent to a zoo because he had become too big to be kept at home. The narrator’s wife, who had got deeply attached to Bruno, was convinced after much effort. The bear was taken to the Mysore zoo after getting a positive response from the curator.

Although the author and his family missed Bruno greatly; but in a sense they were relieved. However his wife was inconsolable. She wept and fretted and wouldn’t eat anything. Meanwhile, reports from the curator and the friends of the narrator who visited the zoo, reported that Bruno, though he was well, was sad too and was not eating anything. After three months, at the insistence of his wife, the author took her to the zoo.

Bruno at once recognized the author’s wife and expressed delight by howling with happiness. After spending three hours feeding and pampering Bruno, the author’s wife requested the curator to give Bruno back to her. He, in turn, recommended her to contact the superintendent. Finally, with the Superintendent’s permission, Bruno was brought home. In order to keep him comfortable and safe, an island with a dry pit or moat around it was made especially for him. The author’s wife would spend a lot of time on the island with Bruno sitting in her lap. This indicated that sloth bears too have affection, memory and individual characteristics.

The Bond of Love Title

The Bond of Love is a perfect example of how love begets love. Even animals understand the language of love. They respond to love in equal measure. The author’s wife loves her pet bear like a child and takes care of his needs. The love given to Bruno by her is reciprocated by him in equal measure. When he is sent to the zoo, both the narrator’s wife and Bruno fret, refuse food and pine for each other. When she goes to see him, Bruno recognises her even after a gap of three months. Thus, we can see the author’s wife and Bruno share a deep bond of love. The title is therefore quite apt.

The Bond of Love Setting

The story The Bond of Love starts from the sugarcane fields near Mysore where the female sloth-bear is shot by one of the narrator’s companions and he brings the bear cub home. The scene now shifts to the narrator’s home in Bangalore whereas he grows in size, there is not much space for BrunoHe is then sent to the Mysore zoo. Finally, after Bruno is brought back because the author’s wife and Bruno were pining for each other. Bruno was kept on a special twenty feet long and fifteen feet wide island made for Bruno in the narrator’s compound in Bangalore. It was surrounded by a dry pit, or moat, six feet wide and seven feet deep. A wooden box that once housed fowls was brought and put on the island for Bruno to sleep in at night.

The Bond of Love Theme

The Bond of Love focuses on the mutual love between an animal and a human being. The author wants to say that animals, too, understand the language of love. The relationship between the bear and the author’s wife proves it. Bruno, the bear, is loved dearly by the author’s wife and he loves her in equal measure.

When he is sent away to a zoo, he frets, looks sad and refuses to eat. The author’s wife, too, does not eat. She visits Bruno in the zoo after a gap of three months, and he recognises her at once. He expresses his pleasure on seeing her by standing on his head. Thus, the bond of mutual love that exists between human and animal is too strong to be broken by time or distance.

The Bond of Love Message

The story conveys the message of the need of showing kindness to animals for they too are creatures created by the same God who created human beings. Animals have a right to dignified and free life. Kenneth Anderson’s friend kills the sloth bear, Bruno’s mother, wantonly. This senseless act leaves the bear cub alone. Thus, human beings being superior in intelligence and evolution, have a special responsibility towards animals and birds, pet or wild.

Animals also experience the feelings of love, joy, pain and separation just like human beings. When Bruno is sent to the zoo, the narrator’s wife weeps and frets, especially when she hears her Baba is inconsolable in Mysore and is refusing food. Bruno is delighted when he sees her and stands on his head to show his pleasure. Thus animals are equally devoted and loyal in reciprocating the love human beings give them.

The Bond of Love Characters

Bruno

Bruno, the pet sloth bear, is affectionate, emotional, sensitive, and playful. Through him the author reveals that animals are sensitive beings with emotions akin to human emotions. Once the bear cub, Bruno, is brought to the family and presented to the lady of the house as a pet, he behaves like a member of the family with a specifically deep bond of love for the author’s wife. He runs about the house, even sleeping in the author’s bed.

Bruno is a very loving bear. He quickly makes friends with the Alsatian dogs and the children of the tenants. He loves the narrator and his family. So much so that when he is sent to the zoo in Mysore, he is inconsolable. He refuses to eat anything and looks thin and sad. Bruno’s selfless love is evident when he is sent to the zoo where he suffers the pain of separation. He frets and refuses to eat. He is overjoyed when he sees the narrator’s wife after three months. He stands on his head to show his pleasure on seeing her.

Bruno is playful and full of life. He entertains everyone by his tricks. He spends his time in playing, running into the kitchen and going to sleep in the beds of the narrator’s family. And he knows a few tricks, too. At the command, ‘Baba, wrestle’, or ‘Baba, box,’ he vigorously tackles anyone who comes forward for a rough and tumble. If he is given a stick and ordered ‘Baba, hold gun’, he points the stick like a gun. If one asks him, ‘Baba, where’s baby?’ he immediately produces and cradles a stump of wood.

Bruno is mischievous and inquisitive. On one occasion, Bruno eats barium carbonate which is kept in the kitchen to kill rats. He is paralysed and has to be taken to a vet. On another occasion, he drinks up old engine oil.

The Author’s Wife

The author’s wife, who is not given any name in the story, is the caretaker of the sloth bear, whom she names Bruno and later on affectionately calls ‘Baba’. She is an embodiment of love, care, concern, consideration and kindness. She is delighted when her husband gifts her a young cub of a sloth bear. She is selfless and highly affectionate and takes good care of the pet as if he were her own child. It is due to her love and care that the pet bear survives despite losing his mother. She takes him into her family and calls him ‘Baba’ which in Hindi means a ‘young boy’. Because of her affection, he becomes playful and fun-loving. She is kind and gentle with animals as is evident not only in the love with which she brings up Bruno, but also the fact that she has two pet Alsatians too.

However, she is considerate and does not resent putting him in chains for the sake of the children of the tenants. She also agrees to have him sent to a zoo when he grows too big and unmanageable. She is terribly sad at being separated from him. Like a real mother, she carries food for him when she visits him at the zoo. She is so overwhelmed by seeing Bruno’s sorrow at being separated from her that she is able to convince the curator and the Superintendent that he should be sent back home. She is delighted to have him back and makes the pet sit in her lap although he has grown big.

She is sentimental and when Bruno is sent to the zoo, she preserves the stump and the bamboo stick with which he used to play and returns them to him when he comes back.

The Bond of Love Summary Questions and Answers

Question 1.

How did the author get the baby sloth bear?

Answer:

The author got the baby sloth bear in a freak accident. Once the author and his friends were passing through the sugarcane fields near Mysore, Bruno’s mother was wantonly shot dead by one of his companions. The cub was found moving on the body of his mother. It was in great shock and tried to flee but the author managed to capture it, and bring it home.

Question 2.

Why did the author not kill the sloth bear when she appeared suddenly?

Answer:

Being kind-hearted, the author did not kill any animals without any motive or provocation. As the sloth bear had not provoked or attacked him, he did not kill it. That is why he describes his companions shooting of her a wanton act.

Question 3.

Why did one of the author’s companions kill the bear?

Answer:

One of the author’s companions killed the bear wantonly, in a moment of impulsive rush of blood. He may have though the bear would attack them and he may have shot it as an impulsive act bom of self-preservation.

Question 4.

How did the author capture the bear cub?

Answer:

When the bear cub’s mother was shot, it ran around its prostrate parent making a pitiful noise. The author ran up to it to attempt a capture. It scooted into the sugarcane field. Following it with his companions, the author was at last able to grab it by the scruff of its neck and put it in a gunny bag.

Question 5.

How did the author’s wife receive the baby sloth bear?

Answer:

The author’s wife was extremely happy to get the baby sloth bear as a pet. She put a coloured ribbon around his neck and named him Bruno.

Question 6.

How was Bruno, the baby bear, fed initially? What followed within a few days?

Answer:

Initially, the little Bmno was given milk from a bottle. But soon he started eating all kinds of food and drank all kinds of drinks. He ate a variety of dishes like porridge, vegetables, nuts, fruits, meat, eggs, chocolates etc., and drank milk, tea, coffee, lime-juice, buttermilk, even beer and alcoholic liquor.

Question 7.

“One day an accident befell him”. What accident befell Bruno?

Answer:

One day Bmno ate the rat poison (barium carbonate) kept in the library to kill rats. The poison affected his nervous and muscular system and left him paralysed. He rapidly became weak, panted heavily, vomited, and was unable to move.

Question 8.

How was Bruno cured of paralysis?

Answer:

Bmno had mistakenly consumed poison and had got paralysed. However, he managed to crawl to the author’s wife on his stumps. He was taken to the veterinary doctor who and injected 10 cc of the antidote into him. The first dose had no effect. Then another dose was injected which cured Bruno absolutely. After ten minutes of the dose, his breathing became normal and he could move his arms and legs.

Question 9.

Why did Bruno drink the engine oil? What was the result?

Answer:

Once the narrator had drained the old engine oil from the sump of his car and kept it to treat termites. Bruno, who would drink anything that came his way, drank about one gallon of this oil too. However, it did not have any effect on him.

Question 10.

What used to be Bruno’s activities at the author’s home?

Answer:

In the beginning, Bruno was left free. He spent his time in playing, running into the kitchen and going to sleep in our beds. As he grew older, he became more mischievous and playful. He learnt to do a few tricks, too. At the command, ‘Baba, wrestle’, or ‘Baba, box,’ he vigorously tackled anyone who came forward for a rough and tumble. If someone said ‘Baba, hold gun’, he would point the stick at the person. If he was asked, ‘Baba, where’s baby?’ he immediately produced and cradled affectionately a stump of wood which he had carefully concealed in his straw bed.