CA Foundation Business Laws Study Material Chapter 8 Performance of Contract

WHAT IS PERFORMANCE?

Definition: A contract creates legal obligations. “Performance of a contract” means the carrying out of these obligations. Each party must perform or offer to perform the promise which he has made. Sec. 37 para 1, of the Contract Act lays down that:

“The parties to a contract must either perform, or offer to perform, their respective promises, unless such performance is dispensed with or excused under the provisions of this Act, or of any other law.”

In case of death of the promisor before performance, the representatives of the promisor are bound to perform the promise unless a contrary intention appears from the contract.

Illustration – X promises to deliver a horse to Y on a certain day on payment of Rs. 1,000. X dies before that day. X’s representatives are bound to deliver the horse to Y and Y is bound to pay Rs. 1,000 to X’s representatives.

WHAT IS ACTUAL PERFORMANCE & ATTEMPTED PERFORMANCE?

Performance may be:

- Actual performance; or

- Attempted performance or Tender.

(1) Actual Performance

When each party to a contract fulfils his obligation arising under the contract within the time and in the manner prescribed, it amounts to actual performance of the contract and the contract comes to an end or stands discharged.

(2) Attempted Performance or Tender

When the promisor offers to perform his obligation under the contract, but is unable to do so because the promisee does not accept the performance, it is called “attempted performance” or “tender”. Thus, “tender” is not actual performance but is only an “offer to perform” the obligation under the contract. A valid tender of performance is equivalent to performance.

ESSENTIALS OF A VALID TENDER

A valid tender or offer of performance must fulfil the following conditions: (Sec. 38)

- It must be unconditional. (A tender is conditional where it is not in accordance with the term of the contract).

- It must be made at proper time and place.

- It must be of the whole obligation contracted for and not only of the part.

- If the offer/tender relates to delivery of goods, it must give a reasonable opportunity to the promisee for inspection of goods so that he may be sure that the goods tendered are of con-tract description.

- It must be made by a person who is in a position and is willing to perform the promise.

- It must be made to the proper person i.e., the promisee or his duly authorised agent. Tender made to a stranger is invalid.

- If there are several joint promisees, an offer to any one of them is a valid tender.

- In case of tender of money, exact amount should be tendered in the legal tender money.

Exception

If a debtor has properly offered to pay money, and the creditor refuses to accept payment, the debtor’s liability to pay shall not come to an end. However, he will get one relief starting from the date of rejection of the tender. He will not be liable to pay interest on the due amount from the date of rejection.

Effect of refusal of party to perform promise wholly [Sec. 39]

When a party to a contract has refused to perform, or disabled himself from performing his promise in it’s entirely, the promisee may put an end to the contract, unless he has signified, by words or conduct, his acquiescence in its continuance.

Illustrations:

(a) X, a singer enters into a contract with Y, the manager of a theatre to sing at his theatre two nights in every week during the next two months, and Y engages to pay her t 100 for each nights performance. On the sixth night X wilfully absents herself from the theatre. Y is at liberty to put an end to the contract.

(b) If in the above illustration, with the assent of Y, X sings on the seventh night, Y is presumed to have signified his acquiescence in the continuance of the contract and cannot put an end to it; but is entitled to compensation for the damages sustained by him through X’s failure to sing on the sixth night.

BY WHOM MUST A CONTRACT BE PERFORMED? [SECS. 40 & 41 ]

- By promisor himself

If that was the intention of the parties, ie. where personal consideration is the foundation of the contract. (Sec. 40) - By agent

Where personal consideration is not the foundation of contract, a person can perform his obligations through an agent. (Sec. 40) - By legal representatives

In case of death of the promisor, the legal successors are bound to perform the contract, unless the contract is of personal nature. - By joint promisors

When two or more persons have made a joint promise, then unless a contrary intention ap-pears from the contract, ‘- all such persons must jointly fulfil the promise.

- If any of them dies, his legal representative must, jointly with the surviving promisors, fulfil the promise.

- If all the promisors die, the legal representatives of all of them must fulfil the promise jointly.

- Performance by third person

When a promisee accepts a performance of the promise from a third person, he cannot afterwards enforce it against the promisor. (Sec. 41) Acceptance of performance from a third party involves waiver of right of performance by the promisor. According to the Calcutta High Court a consignee after receiving compensation for the loss from an insurer cannot again sue the carrier who was actually liable for causing the loss of goods in transit.

Who can demand performance?

- The promisee

The promise, i.e.; the person who was given the promise, can demand performance. - The agent

The agent can also demand performance on behalf of the promisee. - The legal representative

In case of death of the promisee before performance, his legal representative, can demand performance. - Performance of joint promises

When a person has made a promise to several persons, then, unless a contrary intention appears from the contract, the right to claim performance rests with all of them. When one of the promisee dies, it rests with his legal representatives jointly with the surviving promisees.

When all the promises die, it rests with their legal representatives jointly.

WHEN CONTRACTS NEED NOT BE PERFORMED?

Sections 62 to 67 of the Contract Act are listed under the heading “Contracts which need not be performed”. The relevant provisions are as follows:

- If the parties to the contract agree to substitute a new contract for it or to rescind or alter it, the original contract need not be performed. (Sec. 62).

Where the parties to a contract agree to substitute the existing contract for a new contract, that is called novation. In the well-known case of Scarf v. Jardine (1882) 7 App Cas-345 it was stated that novation is of two kinds,- involving change of parties; or

- involving substitution of a new contract in place of the old. (see next chapter for more details)

- If the promisee dispenses with or remits wholly or in part, the performance of promise made to him or extends the time for such performance or accepts in satisfaction for it, the contract need not be performed. (Sec. 63)

- When a voidable contract is rescinded, the other party need not perform his promise. (Sec. 64).

- “If the promisee neglects or refuses to afford the promisor reasonable facilities for the performance of his promise, the promisor is excused by such neglect or refusal as to any non-performance caused thereby”. (Sec. 67).

Illustration: A contracts with B to repair B’s house. B neglects or refuses to point out to A the places in which his house requires repair. A is excused for the non-performance of the contract, if it is caused by such neglect or refusal.

DEVOLUTION OF JOINT LIABILITIES & JOINT RIGHTS [SECS. 42 TO 45]

Devolution of joint liabilities (Section 42)

When two or more persons have made a joint promise, then, unless a contrary intention appears by the contract, all such persons, during their joint lives, and, after the death of any of them, his representatives jointly with the survivor or survivors and, after death of the last survivor, the representatives of all jointly, must fulfil the promise.

According to this section joint promisors must, during their joint lives, fulfil the promise. And if any of them dies, his representative must, jointly with the surviving promisors, fulfil the promise and so on. On the death of the last survivor, the representatives of all of them must fulfil the promise. But this is subject to any private arrangement between the parties. They may expressly or impliedly prescribe a different rule.

Any one of joint promisors may be compelled to perform [Section 43]

When two or more persons make a joint promise, the promisee may, in the absence of express agreement to the contrary, compel any (one or more) of such joint promisors to perform the whole of the promise.

- Each promisor may compel contribution.— Each of two or more joint promisors may com-pel every other joint promisor to contribute equally with himself to the performance of the promise, unless a contrary intention appears from the contract.

- Sharing of loss by default in contribution.— If any one of two or more joint promisors makes default in such contribution, the remaining joint promisors must bear the loss arising from such default in equal shares.

Illustrations

- A, B and C jointly promise to pay D 3,000 rupees. D may compel either A or B or C to pay him 3,000 rupees.

- A, B and C jointly promise to pay D fee sum of 3,000 rupees. C is compelled to pay the whole. A is insolvent, but his assets are sufficient to pay one-half of his debts. C is entitled to receive 500 rupees from A’s estate, and 1,250 rupees from B.

- A, B and C are under a joint promise to pay D 3,000 rupees. C is unable to pay anything and A is compelled to pay the whole. A is entitled to receive 1,500 rupees from B.

This section lays down three rules:

- Firstly, when a joint promise is made, and there is no express agreement to the contrary, the promisee may compel any one or more of the joint promisors to perform the whole of the promise. “A, B and C jointly promise to pay D 3000 rupees. D may compel either A or B or C to pay him 3000 rupees.” This implies that unless there is a contract to the contrary, each joint-promisor is individually liable for the entire performance. Thus the liability of joint-prom¬isors is joint as well as several “Several” means severable or separable. Several liability of a joint-promisors is a liability which can be separated from the joint liability and becomes an individual liability.

- Secondly, a joint promisor who has been compelled to perform the whole of the promise, may require the other joint promisors to make an equal contribution to the performance of the promise, unless a different intention appears from the agreement. A, B and C are under a joint promise to pay D 3000 rupees. D recovers the whole amount from A. A may require B and C to make equal contributions.

- Thirdly, if any one of the promisors makes a default in such contribution, the remaining joint promisors must bear the deficiency in equal shares. A, B and C are under a joint promise to pay D 3000 rupees, C is unable to pay anything. The deficiency must be shared by A and B equally. If C’s estate is able to pay one-half of his share, the balance must be made up by A and B in equal proportions.

Section 43 allows an action to be brought against any one of the joint promisors without impleading the others as defendants. Suppose now that the creditor sues only one joint promisor, can he subsequently sue the others?

According to the English law he cannot, but according to Indian Law he can subsequently sue the others. The creditor is also given the right to release anyone of the joint promisors from his liability and this does not discharge the others from their liabilities.

Effect of release of one joint promisor [Section 44]

Where two or more persons have made a joint promise, a release of one of such joint promisors by the promisee does not discharge the other joint promisor or joint promisors; neither does it free the joint promisor so released from responsibility to the other joint promisor or joint promisors.

This section gives to the promisee a right to release any one or more of the joint-promisor from the liability under the joint promise. Once the release is granted, the promisee will not be able to file a suit against the released joint-promisor. But, the liability of the other joint-promisor shall continue unchanged. Similarly, the liability of the released joint-promisor towards other joint-promisors for contribution shall also continue. The net result is that there is no substantive gain to the released joint promisor.

This also marks a departure from the English Common Law, according to which a discharge of one joint promisor amounts to a discharge of all, unless the creditor expressly preserves his rights against them.

Devolution of joint rights [Section 45]

When a person has made a promise to two or more persons jointly, then, unless a contrary intention appears from the contract, the right to claim performance rests, as between him and them) with them during their joint lives, and, after the death of any of them, with the representatives of such deceased person jointly with the survivor or survivors, and after the death of the last survivor, with the representatives of all jointly.

Illustration: A, in consideration of 5000 rupees, lent to him by B and C, promises B and C jointly to repay them that sum with interest on a day specified- B dies. The right to claim performance rests with B’s representative jointly with C during Cs life, and after the death of C with the representatives of B and C jointly.

TIME AND PLACE OF PERFORMANCE [SECS. 46 TO 50]

Time and place of performance of a contract are matters to be determined by agreement between the parties themselves. If there is no such agreement, then provisions of sections 46 to 50 apply.

Where no time for performance is specified

Where no time for performance is specified, the promisor must perform the promise within a reasonable time (sec. 46). The question, “what is a reasonable time” is in each particular case, a question of fact.

When a promise is to be performed on a certain day

When a promise is to be performed on a certain day, the promisor may perform it at any time during the usual hours of business on such day and at the place at which the promise ought to be performed (sec. 47)

Illustration: A promises to deliver goods at B’s warehouse on the first January. On that day A brings the goods to B’s warehouse, but after the usual hour for closing it, and they are not received. A has not performed his promise.

If no time and place is fixed for the performance of, the promise

If no time and place is fixed for the performance of the promise, the promisor must apply to the promisee to fix the day and time for performance (secs. 48 & 49)

Illustration: A undertakes to deliver a thousand tons of jute to B on a fixed day. A must apply to B to appoint a reasonable place for the purpose of receiving it, and must deliver it to him at such place.

According to Sec. 50

According to Sec. 50 the performance of any promise may be made in any manner or at any time which the promisee prescribes or sanctions.

RECIPROCAL PROMISES [SECS. 51 TO 54 ANC 57]

According to Sec. 2(f) promises which form the consideration or part of the consideration for each other, are called reciprocal promises. Such promises are mutual promises, Le. a promise for a promise. When one party gives a promise in consideration for the other’s promise, both the promises are called reciprocal promises. For example, in a transaction of sale, there are two reciprocal promises:

- The buyer promises to pay the price and,

- The seller promises to deliver the goods.

Kinds of reciprocal promises

- Mutual and independent promises

Where one party has to perform his promise independently without waiting for the performance or willingness of the other party, the promises are mutual and independent. For example, A agrees to sell the car and deliver the same to B on 1-1-2009 while B agrees to pay the price on 15-1-2009. The promises are independent. - Mutual and dependent

Where the performance of the promise by one party depends upon the prior performance of the promisor or by the other party, the promises are conditional and dependent. For example, X agrees to construct a house for Y. Y agrees to supply cement for building the house. The promises are conditional and dependent. - Mutual and concurrent

Where the two promises are to be performed simultaneously, they are said to be mutual and concurrent.

Rules regarding performance of reciprocal promises [Secs. 51 to 54]

1. When reciprocal promises have to be simultaneously performed the promisor is not bound to perform, unless the promisee is ready and willing to perform his promise. [Sec. 51]

Illustrations:

- A agrees to sell goods to B on cash payment, which B agrees. If A find that B is not ready to pay the cash then and there, he need not sell the goods.

- A and B make a contract for sale of goods, the payment to be made by B in instalments.

Goods are to be delivered on the payment of first instalment. If B is not ready and willing to pay the first instalment, A need not deliver the goods.

2. The reciprocal promises must be performed in the order fixed by the contract. [Sec. 52]

Illustration: A and B contract that A shall build a house for B for a fixed price. A’s promise to build the house must be performed before B’s promise to pay for it.

3. If one party prevents the other party from performing his reciprocal promise, the contract become voidable and the party so prevented can claim compensation. [Sec. 53]

Illustration: A and B contract that B shall execute certain work for A for a thousand rupees. B is ready and willing to execute the work accordingly, but A prevents him from doing so. The contract is voidable at the option of B; and if he elects to rescind it, he is entitled to recover from A compensation for any loss which he has incurred by its non-performance.

4. Where the nature of reciprocal promises is such that one cannot be performed unless the other party performs his promise in the first place, then if the latter fails to perform he cannot claim performance from the other, but must make compensation to the first party for his loss. [Sec. 54]

Illustrations:

- hires B’s ship to take a cargo from Calcutta to Mauritius. A fails to supply the cargo. A cannot force B to perform his obligation. Rather, A has to give compensation to B for any loss that B may suffer by the non-performance of the contract.

- A contracts to construct a building for B. B^was to supply some material necessary in the construction work. B fails to supply the material. A need not construct the building. He may take compensation from B.

5. Reciprocal promise to do things legal and also things illegal – The first is a contract, but the latter is a void agreement. (Sec. 57)

Illustrations:

- A and B agree that A shall sell B a house for Rs. 10,000 but that if B uses it as a gambling house, he shall pay A Rs. 50,000 for it.

The first set of reciprocal promises, namely, to sell the house and to pay Rs. 10,000 for it, is a contract. The second set is for an unlawful object, viz. that B may use the house as a gambling house, and is a void agreement. - A and B agree that A shall pay B 1000 rupees, for which B shall afterwards deliver to A either rice or smuggled opium. This is a valid contract to deliver rice, and a void agreement as to the opium.

TIME AS THE ESSENCE OF CONTRACT

Parties generally fix time for the performance of the contract. What happens if the contract is not performed within the fixed time? Does it become void or voidable?

This will depend upon “whether time was the essence of the contract”. The phrase “time as the essence of the contract” means that performance within time is the most vital condition of the contract. If time is the essence of the contract then the other party can avoid the contract and if it is not, the other party cannot avoid the contract.

When is the time the essence of the contract?

- Whether time is of the essence of the contract, depends upon

- The intention of the parties

- Nature of the transaction

- The terms of the contract Le. if the parties to the contract have expressly agreed that performance within a limited time was necessary;

- Even where a time is specified for the performance of a certain promise, “time may not be of the essence of the contract” and one has to look at the nature and construction of the contract and the intention of the parties in order to ascertain whether “time is of the essence of the contract” or not;

- It is well settled that unless a different intention appears from the terms of the contract, ordi-narily in commercial contracts the time of delivery of goods is of the essence of the contract but not the time of payment of the price;

- In contracts for the purchase of land, usually time is not of the essence of the contract because land values do not frequently fluctuate.

Effects of failure to perform a contract within the stipulated time

Sec. 55 deals with the subject and lays down the following rules:

- Where “time is of the essence of the contract”and there is failure to perform within the fixed time, the contract (or so much of it as remains unperformed) becomes voidable at the option of the promisee. He may rescind the contract and sue for the breach.

- Where “time is not of the essence of the contract”, failure to perform within the specified time does not make the contract voidable. It means that in such a case the promisee cannot rescind the contract and he will have to accept the delayed performance. But he would be entitled to claim compensation from the promisor for any loss caused to him by the delay. This rule is, however, subject to the condition that the promisor should not delay the performance beyond a reasonable time, otherwise the contract will become voidable at the option of the promisee.

- In case of a contract voidable on account pf the promisor’s failure to perform his promise within the agreed time or within a reasonable time, as the case may be, and if the promisee, instead of rescinding the contract, accepts the delayed performance, he cannot afterwards claim compensation for any loss caused by the delay, unless, at the time of accepting the delayed performance, he gives notice to the promisor of his intention to do so.

APPROPRIATION OF PAYMENTS

Appropriation of payment means the application of payment by a creditor to the discharge of same particular debt. When money is paid, it must be applied according to the rule of the payer and not the receiver. Appropriation is a right primarily of the debtor and for his benefit. Sections 59 to 61 lays down 3 rules regarding appropriation of payments.

1. If the debtor indicates

As per section 59, where the debtor, owing several distinct debts indicates at the time of actual payment that the payment should be applied towards the discharge of a particular debt, the creditor must do so. If there are no clear instructions from the debtor but the circumstances of the case imply that the payment should be applied to a particular debt, then the accepted payment must be applied accordingly.

2. If the debt to be discharged is not indicated [Sec. 60]

If the debtor does not indicate, then the creditor may apply the payment at his discretion to any lawful debt. He cannot, however, apply the payment to a disputed or unlawful debt, but he may apply it to a debt which is barred by the law of limitation.

3. Where the debtor does not intimate and the creditor fails to appropriate [Sec. 61]

The payment shall be applied in discharge of the debts in order of time. If the debts are of the same date, the payment shall be applied in discharge of each proportionately.

[Summary: APPROPRIATION OF PAYMENTS: The debtor has at the time of payment, right of choice of appropriating the payment, in default of the debtor; the creditor has the right to appropriate, in default of either, the law will allow appropriation of debts in order of time.] [Rule in Clayton’s Case: Where the parties have a current account between them, appropriation impliedly takes place in the order in which the receipts and payments take place and are entered in the account. The first item on the debit side of the account is discharged or reduced by the first item on the credit side].

ASSIGNMENT OF CONTRACT

Definition

Assignment means transfer. The rights and liabilities of a party to a contract can be assigned under certain circumstances. Assignment may occur

- by act of parties or

- by operation of law.

Rules: The rules regarding assignment of contracts are summarised below:

ASSIGNMENT BY ACT OF THE PARTIES

- Contracts involving personal skill, ability, credit, or other personal qualifications, cannot be assigned Examples: a contract to marry, a contract to paint a picture, a contract of personal service etc.

- The obligations under a contract, i.e., the burden and the liabilities under the contract cannot be transferred. For example, if X owes Y Rs. 100 he cannot transfer the liability to Z, and force Y to collect his money from Z.

Exception: In both cases 1 and 2, the parties to a contract may agree to replace the original contract by a new one under which the obligations of one of the parties are shifted to a new

party. Thus, in the example given above if Y agrees to accept Z as his debtor in place of X, the liability to pay the debt is transferred from X to Z. Such cases are known as Novation. - A contract may be performed through the agency of a competent person, if the contract does not contemplate performance by the promisor personally – Sec. 40. But in this case the original party remains responsible for the proper performance of the obligations under the contract.

- The rights and benefits under a contract (not involving personal skill or volition) can be as-signed. Thus if X is entitled to receive Rs. 500 from Y, he can assign his right to Z where upon Z will become entitled to receive the money from Y. But in this case the assignment is subject to all equities between the original parties. Thus if Y had already paid a portion of the debt to X, he will pay to Z correspondingly less.

- Actionable claims can be assigned but only by a written document. Notice must be given to the debtor. An actionable claim is a claim to any debt or to any beneficial interest. E.g. A money debt.

ASSIGNMENT BY OPERATION OF LAW

Assignment by operation of law occurs in cases of death or insolvency. Upon the death of a party his rights and liabilities under a contract devolve upon his heirs and legal representatives (except in the case of contract involving personal qualifications). In case of insolvency, the rights and liabilities of the person concerned pass to the Official Assignee or the Official Receiver. Assignment by operation of law occurring upon the death of a party is known as succession.

Distinction between succession and assignment

In succession, the benefits of a contract are succeeded to by a process of law to the legal heirs. Here both, the burden and benefits attaching to the contract devolve on the legal heir. When a son succeeds to the estate of his deceased father he is liable to pay the debts and liability of his father, to the extent of property inherited by him.

In case of assignment, however the benefits of a contract can only be assigned and not the liabilities thereunder. This is because when liability is assigned, a third party gets involved therein. Thus, a debtor cannot relieve himself of the liability to creditor by assigning to someone else his obligation to repay the debt.

|

Basis of distinction |

Succession |

Assignment |

|

1. Meaning |

The transfer of rights and liabilities of a deceased person to his legal representative is called as succession. | The transfer of rights by a person to another person is called as assignment. |

|

2. Time |

Succession takes place on the death of a person. | Assignment takes place during the lifetime of a person. |

|

3. Voluntary act |

Succession is not a voluntary act. It takes place automatically by operation of law. | Assignment is a voluntary act of the parties. |

|

4. Written document |

Succession may take place even without any written document. | Assignment requires execution of an assignment deed. |

|

5. Scope |

All the rights and liabilities of a person are transferred by way of sufccession. | Only rights can be assigned liabilities, under a contract, cannot be assigned unless there is novation. |

|

6. Notice |

No notice of succession is required to be given to any person. | Notice of assignment must be given to the creditor. |

|

7. Consideration |

No consideration is necessary for succession. | Consideration between assignor and assignee is a must for assignment. |

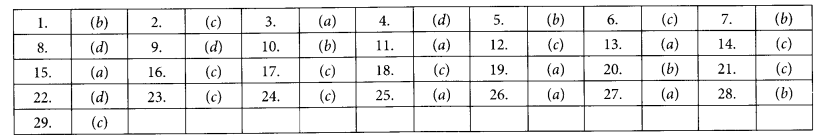

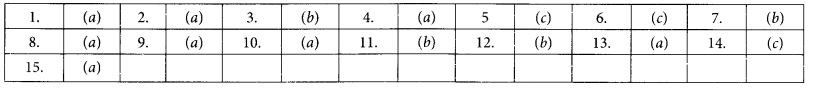

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS:

1. Where a party to a contract fails to perform at or before a specified time and it was the intention of the parties that time should be of the essence,

(a) The contract becomes voidable

(b) The contract does not become voidable but the aggrieved party is entitled to compensation

(c) The contract becomes void

(d) None of these

2. A owes B Rs. 1,000 but the debt is barred by the Limitation Act. A signs a written promise to B for Rs. 500 on account of the debt. This is a :

(a) Valid contract

(b) Voidable contract

(c) Void contract

(d) Unenforceable agreement

3. A contracts with B to construct a building for a fixed price, B supplying the necessary timber. This reciprocal promise is :

(a) Mutual and Independent

(b) Mutual and Dependent

(c) Mutual and Concurrent

(d) None of the above

4. A contract of personal nature can be performed by:

(a) The promisor,

(b) The agent,

(c) The legal representative,

(d) None of the above.

5. Liability of the joint promisor is :

(a) Joint

(b) Several

(c) Joint and several

(d) None of the above

6. If neither the debtor nor the creditor appropriates the payment, the payment will be appropriated:

(a) As per the desire of the promisor,

(b) As per the desire of the promisee,

(c) In order of time,

(d) None of the above.

7. Agreement by way of wager are

(a) Valid and enforceable by law

(b) Void

(c) Voidable at the option of party

(d) Illegal

8, A, a singer enters into a contract with B, the manager of a theatre to sing at his theatre two nights in every week during the next two months and B engages to pay her Rs. 100 for each night’s performance. On the sixth night, A wilfully absents herself from the theatre.

(a) B is at liberty to put an end to the contract

(b) B cannot put an end to the contract

(c) The contract is left at the liberty of A

(d) None of these

9. A and B contract to marry each other before the time fixed for the marriage. A goes mad. The contract becomes :

(a) Void

(b) Voidable

(c) Unenforceable

(d) None of these

10. If a contract is based on personal skill or confi¬dence of parties, the death of a party in such a case :

(a) Puts an end to the contract

(b) Does not put an end to the contract

(c) The representatives of the deceased can be made liable to perform such a contract

(d) None of these

11. A modification or revocation of the contract requires a of each contracting party.

(a) Denial

(b) Consensus

(c) Modification

(d) Revocation

12. If the performance of contract becomes impos¬sible because the subject matter of contract has ceased to exist then :

(a) Both the parties are liable

(b) Neither party is liable

(c) Only offerer is liable

(d) Only acceptor is liable

13. A doctor teaching in a medical college pre-vented from doing private practice, such a restriction is :

(a) Valid

(b) Partial lawful

(c) Unlawful

(d) Partial Unlawful

14. A contracts to sing for B for a consideration of Rs. 5,000 which amount is paid in advance. A becomes unwell and is not able to perform. B suffers a loss of Rs. 10,000. A is liable to pay B

(a) Rs. 15,000

(b) Rs. 10,000

(c) Rs. 5,000

(d) Nothing

15. A promises to deliver goods at B’s warehouse on the 1st January. On that day, A brings the goods to B’s warehouse but after the usual hour for closing it and they are not received. Which one of the following is correct?

(a) A has not kept his promise

(b) A kept his promise as time was not specified

(c) A performs his duty as the time is not the essence of the contract

(d) All of these

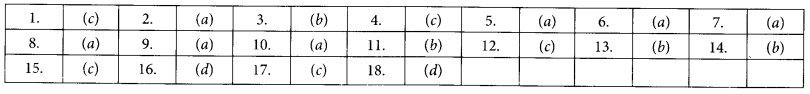

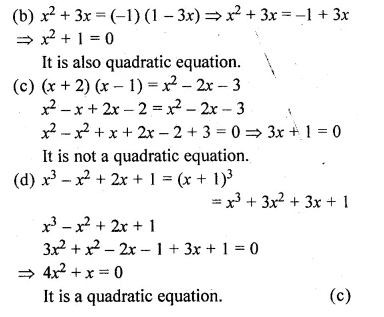

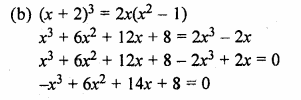

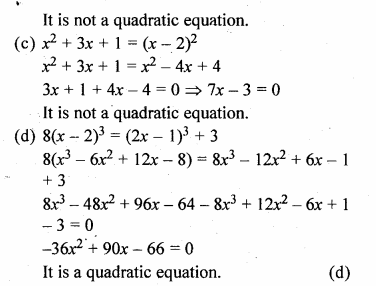

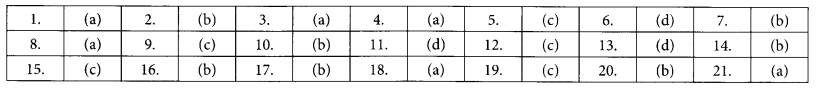

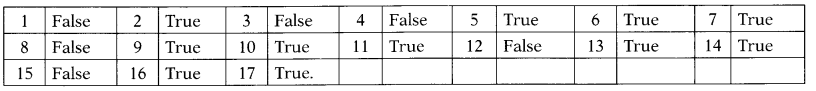

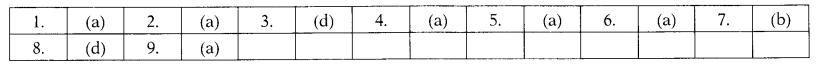

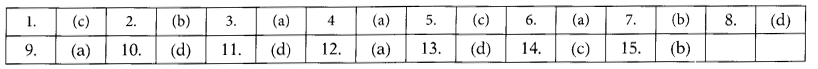

Answers:

STATE WHETHER THE FOLLOWING ARE TRUE OR FALSE:

1. When a promisee neglects to give the promisor reasonable facilities for the performance of a promise, the promisor is still liable for performance.

2. Under the Contract Act the liability of joint promisors is joint as well as several.

3. A contract involving the exercise of personal skill, volition or credit can also be performed by an agent or a legal representative.

4. A debtor sends a payment but the creditor refuses to accept it. Even then the debtor is not discharged from the debt.

5. The promisee may compel any one of the joint promisors to perform the promise.

6. A debtor while making the payment expressly informs the creditor that the payment should be applied to particular debt, the creditor is not bound to do so.

7. A release of one promisor does not discharge the other joint promisors.

8. In a contract where time is the essence of the contract, if the promisor fails to perform in time, the contract becomes void.

9. A legal representative of a deceased promisee can demand performance of a contract under all circumstances.

10. In the absence of the debtor’s intimation to the creditor regarding appropriation of a payment, the cred¬itor can utilise the payment even towards payment of a time-barred debt.

11. In case of joint promise by two or more persons, the promisee may compel any of such joint promisors to perform the whole of the promise.

12. If a party to a contract has promised to do certain things, at a particular time, and fails to do by that time, the contract shall become voidable at the option of the promisee.

13. Performance of the contract may be made only by the parties to the contract.

14. If one of the joint promisors is made to perform the whole contract, he can ask for equal contribution from others.

15. The burden of the contract cannot be assigned without the consent of the other party or parties of the contract.

16. A promise under a contract can be performed by the promisor himself.

17. When the promisee does not accept the offer of performance, the promisor is not responsible for the non-performance.

18. Payments made by a debtor are always appropriated in a chronological order.

19. If the promisees are joint, the right to claim performance is joint and not joint and several.

20. It is mixed question of law and fact whether time was the essence of the contract.

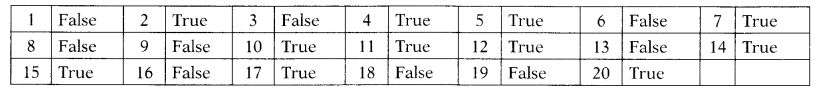

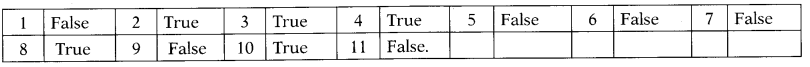

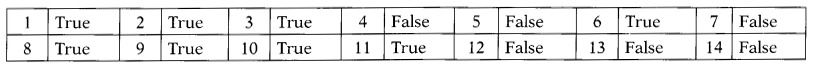

Answers: