CA Foundation Business Laws Study Material Chapter 7 Contingent Contracts and Quasi Contracts

WHAT IS A CONTINGENT CONTRACT?

Definition

“A contingent contract is a contract to do or not to do something, if some event, collateral to such contract, does or does not happen” – [Section 31]. Contracts of insurance, indemnity and guarantee are examples of contingent contract.

Meaning of Collateral Event

According to Pollock and Mulla, collateral event means an event which is, “neither a performance directly promised as part of the contract, nor the whole of the consideration for a promise For e.g. A contracts to pay B Rs. 1,00,000 if B’s house is burnt. This is a contingent contract, because the burning of B’s house is neither a performance promised as part of the contract nor it is the consideration obtained from B. The liability of A arises only on the happening of a collateral event which is an independent event but collateral to the main contract.

- A contract can also be contingent if it depends on act of a party to the contract or that of a third person. For example, a promise to purchase a computer if the managing director of the company approves it is a valid contract. A entered into a contract for the supply of timber to the Govt. One of the terms of the contract was that the timber would be rejected if it is not approved by the Superintendent of the Gun Carriage Factory for which the timber was required. The timber supplied was rejected. A filed a suit for breach of contract. Will he succeed?

- However, if the contingent event depends on the mere will and pleasure of one of the parties to the contract, it would not be valid. Thus, in a contract of service to pay as the employer pleases is no promise.

- The collateral event should not be a part of the reciprocal promises forming the contract. Thus, A agrees to construct a swimming pool for B for Rs. 80,000. The payment is to be made by B only on the completion of the pool. It is not a contingent contract, because these are mutual promises forming part of the contract.

- Where a contract provides that the goods would be delivered as and when they arrive, is not a contingent contract but it merely provides a particular mode of performance.

ESSENTIALS OF CONTINGENT CONTRACTS

- ]The performance of such contracts depends on a contingency Le., on the happening or non-happening of the future event.

- The event must be collateral i.e., incidental to the contract.

- The event must be uncertain. If the event is bound to happen the contract is due to be per¬formed in any case then it is not a contingent contract.

- The contingent event should not be the mere will of the promisor.

RULES REGARDING CONTINGENT CONTRACTS

Sections 32 to 36 of the Contract Act contain certain rules regarding contingent contract, they are summarised below:

Rules regarding contingent contract

1. Sec. 32: Dependent on the happening a future uncertain event

enforceable, when that event happens.

The happening of a future uncertain event: Contracts contingent upon the happening of a future uncertain event, cannot be enforced by law unless and until that event has happened, If the event becomes impossible, such contracts become void. [Sec 32]

Illustrations: A makes a contract with B to buy B’s horse if A survives C. This contract cannot be enforced by law unless and until C dies in A’s lifetime.

Illustrations: A contracts to pay B a sum of money when B marries C. C dies without being : married to B. The contract becomes void.

Illustrations: Where a car was insured against loss in transit, the car was damaged without being put in the course of transit, the insurer was held to be not liable.

2. Sec. 33: Dependent on non-happening of an uncertain future event.

enforceable, when the happening of that event becomes impossible, and not before.

The non-happening of an uncertain future event: Contracts contingent upon the non-happen¬ing of an uncertain future event, can be enforced when the happening of that event becomes impossible and not before. [Sec. 33]

Illustrations: A agrees to pay B a sum of money if a certain ship does not return. The ship is sunk. The contract can be enforced when the ship sinks.

Illustrations: A agrees to pay sum of money to B if a certain ship does not return. The ship, returns back. The contract has become void.

3. Sec. 35(1): Dependent on the happening of an event within a fixed time

enforceable, if the event happens within that time.

The happening of an event within a fixed time: Contracts contingent upon the happening of an event within a fixed time become void if, at the expiration of the fixed time, such event has not happened or if, before the time fixed, such event becomes impossible. [Sec. 35(1)]

Illustrations: A promises to pay B a sum of money if a certain ship return within a year. The contract may be enforced if the ship return within a year, and becomes void if the ship is burnt within a year (since the event becomes impossible).

4. Sec. 35(2): Dependent on the non-happening of an event within a fixed time.

enforceable, if the event does not happen or becomes impossible within that time.

The non-happening of art event within a fixed time: Contracts contingent upon the non-hap- pening of an event within a fixed time may be enforced by law when the time fixed has expired and such event has not happened, or before the time fixed has expired, if it becomes certain that such event will not happen. [Sec. 35(2)]

Illustrations: A promises to pay B a sum of money if a certain ship does not return within a year. The contract may be enforced if the ship does not return within the year, or is burnt within a year.

5. Sec. 34: Dependent on the future conduct of a person acting in a particular way

enforceable, if that person acts in that way or

the future conduct of any person is considered impossible, if that person does something which makes it impossible to perform in the given circumstances.

When event to be deemed impossible if it is the future conduct of a living person: If a contract is contingent upon how a person will act at an unspecified time, the event shall be considered to become impossible when such person does anything which renders it impossible that he should so act within any definite time, or otherwise than under further contingencies. [Sec. 34]

In other words, if a promise depends on the act of a third party, it will become void should such third party refuse to do the act or if he incapacitates himself from doing it. For e.g. S sells goods to B and B promises to pay the price after C has fixed it. If C refuses to fix the price or if he dies before fixing it, the agreement becomes void.

Illustration: A agrees to pay B a sum of money if B marries C. C marries D. The marriage of B to C must now be considered impossible although it is possible that D may die and that C may afterwards marry B.

Illustrations: In Frost v. Knight, the defendant promised to marry the plaintiff on the death of his father. While the father was still alive, he married another woman. It was held that it had become impossible that he should marry the plaintiff and she was entitled to sue him for the breach of the contract.

6. Sec. 36: Dependent on an impossible event.

is void ab initio.

Impossible event: Contingent agreements to do or not to do anything, if an impossible event happens, are void, whether the impossibility of the event is known or not to the parties to the agreement at the time when it is made. [Sec. 36]

Illustrations: 1. A agrees to pay B Rs. 1,000 if two straight lines should enclose a space. The agreement is void.

Illustrations: 2. A agrees to pay B Rs. 1,000 if B will marry A’s daughter C. C was dead at the time of the agreement. The agreement is void.

A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN CONTINGENT CONTRACT AND WAGERING AGREEMENTS:

|

Wagering Agreements |

Contingent Contracts |

| 1. A wagering agreement is void. | 1. A contingent contract is valid. |

| 2. A wagering agreement consists of reciprocal promises. | 2. Contingent contract may not contain reciprocal promises. |

| 3. In a wagering agreement the parties have no interest in the subject matter of the contract. | 3. In a contingent contract either party may have interest in the subject matter of the contract. |

| 4. In a wagering agreement the future event is the sole determining factor. | 4. In a contingent contract the future event is only collateral and incidental. |

| 5. Every wagering agreement is of a contingent nature. | 5. Every contingent contract is not of a wagering nature. |

QUASI CONTRACT : WHAT IT IS?

The term ‘Quasi’ means ‘as if’or ‘similar to’. A quasi-contract is similar to a contract. Just like a contract it also creates legal obligations. But the legal obligations created by quasi contract do not rest on any agreement but are imposed by law. It is therefore, contractual in law, but not in fact.

A Quasi Contract can be defined as a fictional contractual obligation created by law, in certain circumstances. (In the absence any mutual agreement between the parties.)

In reality it is not a contract since the essential elements of contract like offer and acceptance, lawful consideration etc. are not present. It is an obligation which the law creates in the absence of any agreement, when the acts of the parties or others have placed in the possession of one person, money or its equivalent, under such circumstances that in equity and good conscience he ought not retain it, and which ex aqeuqo bono (in justice and fairness) belongs to another. Quasi contract is fictitiously deemed contractual, in order to fit the cause of the action to the contractual remedy.

The Indian Contract Act describes quasi contract as ‘certain relations resembling those created by contracts’.

BASIS OF QUASI CONTRACT

Quasi contracts are based on principles of equity, justice and good conscience. They aim at prevention of “unjust enrichment” i.e. no man shall be allowed to enrich himself at the cost of another.

Another theory regarding the judicial basis of such contract is that it is implied, notional or fictional contract imputed by law out of equitable considerations.

The salient features of quasi-contractual right are as follows:

- Such a right is always a right to money, and generally, though not always, to a liquidated sum of money,

- It does not arise from any agreement of the parties concerned, but is imposed by the law,

- It is a right which is available not against all the world, but against a particular person or person only, so that in this respect it resembles a contractual right, &

- Damages can be claimed for breach of quasi-contractual right.

TYPES OF QUASI CONTRACTS

Sections 68 to 72 of the Contract Act deals with five different types of quasi contracts. In each of these cases there is no real contract between the parties, but due to peculiar circumstances in which they are placed, the law imposes in each of these cases a contractual liability.

(1) Claim for necessaries supplied to persons incapable of contracting [Sec. 68]

If necessaries are supplied to a person who is incapable of contracting, e.g., a minor or a person of unsound mind, the supplier is entitled to claim their price from the property of such a person.

Sec. 68 states “If a person, incapable of entering into a contract, or any one whom he is legally bound to support, is supplied by another person with necessaries suited to his condition in life, the person who has furnished such supplies is entitled to be reimbursed from the property of such incapable person. ”

Accordingly, if A supplies to B, a lunatic, necessaries suited to B’s status in life, A would be entitled to recover their price from B’s property. He would also be able to recover the price for necessaries supplied by him to his (B’s) wife or minor child since B is legally bound to support them. However, if B has no property, nothing would be realizable. It should, however, be noted that in such circum¬stances, the price only of necessaries and not of article of luxury, can be recovered.

(2) Right to recover money paid for another person [Sec. 69]

A person who has paid a sum of money which another is obliged to pay, is entitled to be reimbursed by that other person provided the payment has been made by him to protect his own interest.

Example: B holds land in Bengal, on a lease granted by A, the Zamindar. The revenue payable by A to the Government being in arrears his land is advertised for sale by the Government. Under the revenue law the consequences of such sale will be annulment of B’s lease. B to prevent the sale

and the consequent annulment of his own lease, pays to the Government the sum due from A. A is bound to make good to B the amount so paid.

Conditions: The following are the conditions mentioned in Sec. 69.

- The payment made should be bona fide for the protection of one’s interest.

- The payment should not be a voluntary one.

- The payment must be such as the other party was bound by law to pay.

(3) Obligation of a person enjoying benefits of non-gratuitous act [Sec. 70]

Such an obligation arises under the provision of Section 70 reproduced below:

“Where a person lawfully does anything for another person, or delivers anything to him not intending to do so gratuitously, and such other person enjoys the benefit thereof, the latter is bound to make compensation to the former in respect of, or to restore, the thing so done or delivered”.

It thus follows that for a suit to succeed, the plaintiff must prove:

- That he had done the act or had delivered the thing lawfully,

- That he did not do so gratuitously, and

- That the other person enjoyed the benefit.

Examples:

- A, a tradesman, leaves goods at B’s house by mistake. B treats the goods as his own. He is bound to pay for them to A.

- A saves B’s property from fire. A is not entitled to compensation from B, if the circumstances show that he intended to act gratuitously.

(4) Responsibility of a finder of goods [Sec. 71]

“A person who finds goods belonging to another and takes them into his custody, is subject to the same responsibility as a bailee”.

Conditions:

- A person who finds goods and takes possession of it is responsible as a bailee.

- That is, he is liable—

- To try and find out the true owner and

- To take due care of the property [Sec. 151]

- Finder is entitled to a lien until paid compensation, but cannot file a suit to recover such compensation.

- Finder is entitled to possession against all except the true owner.

- When owner declares reward, finder can sue for reward.

- Right of re-sale: If the owner is not found or if he refuses to pay lawful charges, the finder may sell—

- When the thing is in danger of perishing or losing the greater part of its value.

- When the lawful charges amount to two-thirds of its value.

Example: Hollins vs. Howler L. R. & H. L., H picked up a diamond on the floor of F’s shop and handed over the same to F to keep till the owner was found. In spite of best efforts, the true owner could not be traced. After the lapse of some week, H tendered to F the lawful expenses incurred by him and requested to return the diamond to him. F refused to do so. Held, F must return the diamond to H as he was entitled to retain goods found against everybody except the true owner.

(5) Liability for money paid or thing delivered by piistake or under coercion [Sec. 72]

“A person to whom money has been paid, or anything delivered by mistake or under coercion must repay or return it (Sec. 72)”. Thus, a payment made by A to B under the mistaken belief that he is liable in respect of a municipal tax on a mis-construction of the terms of the lease, can be recovered from the municipal authorities.

Examples:

A and B jointly owe Rs. 100 to C. A alone pays the amount to C & B, not knowing this fact, pays Rs. 100 over again to C. C is bound to pay the amount to B.

A railway company refuses to deliver up certain goods to the consignee, except upon the payment of an illegal charge for carriage. The consignee pays the sum charged in order to obtain the goods. He is entitled to recover as much of the charge that is illegally excessive.

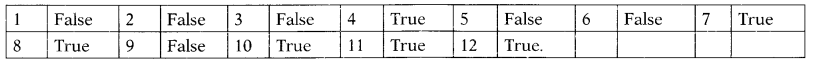

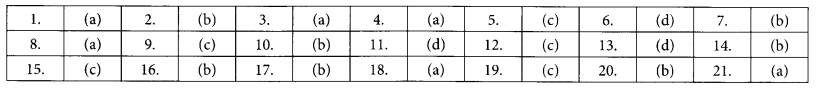

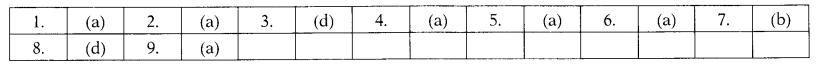

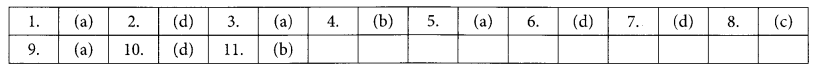

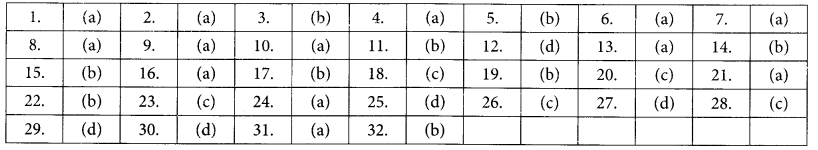

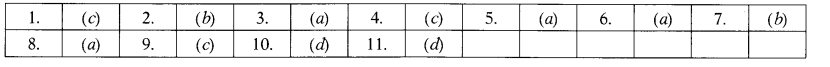

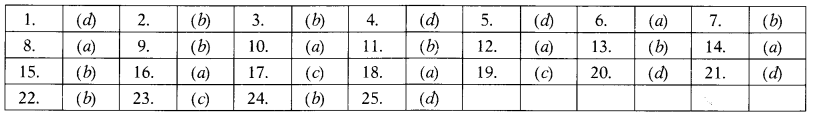

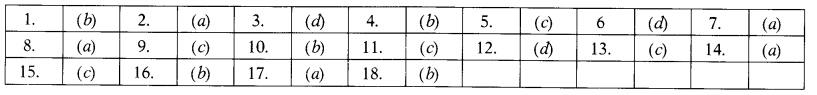

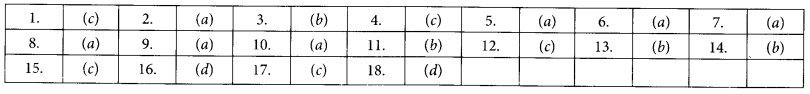

MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS:

1. A makes a contract with B to buy B’s horse if A survives C. This is

(a) a Quasi-contract

(b) a Void contract

(c) a Contingent contract

(d) a Conditional contract

2. An insurance contract is—

(a) Contingent contract

(b) Wagering agreement

(c) Unenforceable contract

(d) Void contract

3. If the contingent depends on the mere will of the promisor it would be—

(a) Valid

(b) Void

(c) Illegal

(d) Depends on the circumstances

4. A contract of life insurance, the performance of which depends upon a future event falls under the category of

(a) Contract of Indemnity

(b) Contract of Guarantee

(c) Contingent Contract

(d) Special type of Contract

5. Which one of the following is not an essential feature of a wagering agreement?

(a) Insurable interest

(b) Uncertain event

(c) Mutual chances of gain or loss

(d) Neither party to have control over the event

6. The contingent contract dependent on the happening of the future uncertain event can be enforced when such event:—

(a) Happens

(b) Does not happen

(c) Does not become a impossible

(d) Both (a) & (c)

7. Contract contingent upon the happening of a future uncertain event becomes void.

(a) If the event becomes impossible

(b) If the event happens

(c) If the event does not happen

(d) None of the above.

8. Contracts contingent upon the non-happening of the future uncertain event becomes void when such event:—

(a) Happen

(b) Does not happen

(c) The event becomes impossible

(d) None of the above

9. Contract contingent upon the non-happening of the future uncertain event becomes enforceable

(a) When the happening of that event becomes impossible and not before

( b) When the happening of that event becomes possible and not before

(c) When the event happens

(d) None of the above.

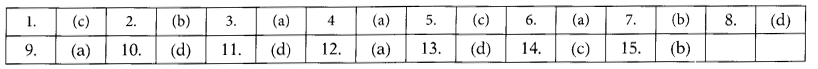

10. A promises to pay B a sum of money if a certain ship does not return within a year. The ship is sunk within a year. The contract is

(a) Enforceable

(b) Void

(c) Voidable

(d) Illegal

11. Contingent contract to do or not to do anything, if an impossible event happens are:—

(a) Valid

(b) Void

(c) Voidable

(d) Illegal

12. Contingent contract dependent on the non-hap-pening of the event within a fixed time can be enforced, if the event:—

(a) Does not happen within the fixed time

( b) Before the time fixed such event becomes impossible

(c) Both (a) & (b)

(d) None of the above

13. In a contingent contract which event is contingent—

(a) Main event

(b) Collateral event

(c) Both (a) & (b)

(d) None of the above.

14. Under section 70 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, if a person who enjoys the benefit of any other person’s work, the beneficiary must pay to the benefactor for the services rendered, provided the intention of the benefactor was :

(a) Gratuitous

(b) Non-gratuitous

(c) To create legal relations

(d) None of these

15. A finder of goods can:

(a) file a suit to recover his expenses,

( b) sell the goods if he likes,

(c) can sue for a reward, if any.

(d) None of the above.

16. A finder of goods can sell the goods if the cost of finding the true owner exceeds:

(a) 1/4 of the value of the goods,

(b) 1 /3 of the value of the goods,

(c) 1 /2 of the value of the goods,

(d) 2/3 of the value of the goods.

17. The contract uberrimae fidei means a contract

(a) Of goodwill

(b) Guaranteed by a surety

(c) Of utmost good faith

(d) Of good faith

18. A finder can sell the goods if:

(a) the goods are ascertained,

(b) the goods are un-ascertained,

(c) the goods are valuable,

(d) the goods are perishable.

Answers:

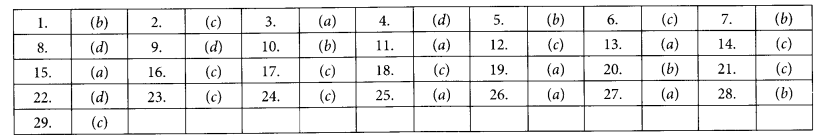

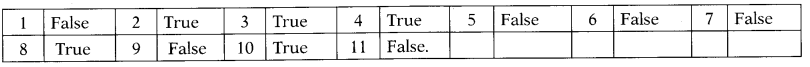

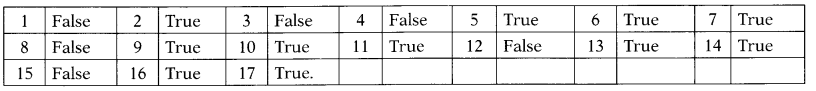

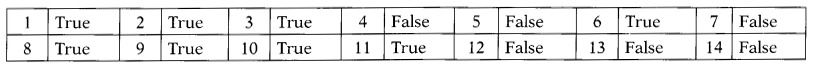

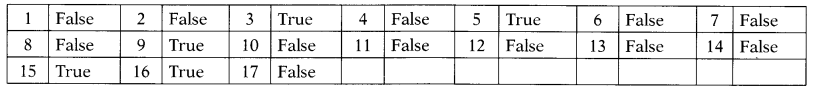

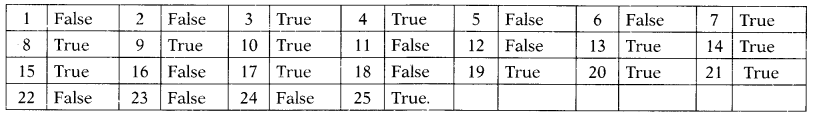

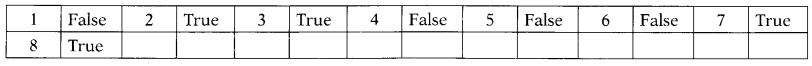

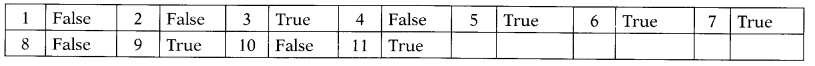

STATE WHETHER THE FOLLOWING ARE TRUE OR FALSE:

1. The event in a contingent contract may be certain or uncertain.

2. A contract of insurance is not a contingent contract.

3. A wagering agreement is a contingent contract.

4. Contracts of indemnity are contingent contracts.

5. Contracts contingent upon the happening of an uncertain specified event within a fixed time can become void only after the expiry of the fixed time.

6. A finder of goods can sue the true owner for recovery of expenses incurred for the safety of the goods.

7. Any person making payment for another can get reimbursement from the person for whom he has paid.

8. A person supplying articles of the necessities to the wife of a lunatic is entitled for reimbursement from the property of the lunatic.

9. A person cannot recover from another an amount paid under a mistake of law.

10. A person who enjoys the benefit of a non-gratuitous act is bound to make compensation.

11. A finder of lost goods is a bailee.

12. In Quasi-contract the promise to pay is always an implication of law and not of facts.

Answers: